What of the bow?

The bow was made in England:

Of true wood, of yew wood,

The wood of English bows:

So men who are free

Love the old yew tree

And the land where the yew tree grows.

-Sir A. Conan Doyle

I was six, just turning seven and Holy Trinity Convent was a large stately brick house girdled by lawns and pathways that undulated to the skirt of a large wood. I walked to school every day with my mother, first down the road from my house, then through the slip, a country lane, that eventually popped onto a traffic busy road. Holy Trinity lay across the street. I was to begin first grade and I was excited to meet Miss Parker. She reminded me of a comfortable old armchair. She was warm and soft. She styled her salt and peppery hair in a soft upturned roll. She wore brown corduroy jackets and brown/grey kilts and sensible lace-up shoes built for a good walk. She was big and handsome, and had a warm low husky voice. And she was kind. She lived in the gatehouse with her friend Miss Dickinson who was completely opposite in temperament and whom we were doomed to meet as a teacher the following year. However, we girls had the benefit of being inducted into Junior school by the best of all possible teachers who would nourish our little bones so we could withstand the ice storm that waited for us.

First day of Junior I, after morning prayers, I sat in my desk and breathed the incense that seeped through the floor boards from the chapel below. Miss Parker entered the room. We stood. Hardly able to contain our excitement for what was about to happen. We held our breaths. Yes. This was THE room. The walls were squares of Tudor wood paneling except where the chalkboards and the windows were situated. “Bonnes filles du matin”, (Good morning, girls) she said in her warm brown voice. “Bonjour, Mlle Parker”, we replied. Then she slowly walked around the room knocking on each wood panel close to the floor. Each panel resounded with a soft “thuck-thuck”. We held our breaths, there it was…a hollow “thunk” and we cheered! She opened the priest’s hole which was two panels tall and shone her flashlight into a small passageway that descended into the gloom.

The panel to the priest’s hole was locked from behind after that day. None of us ever touched it but we lived side by side with it as we read our science, did our sums, and struggled clumsily with our French lessons. Miss Parker explained that the passageway led to tunnels underneath the grounds outside and then to the catacombs that ran from the grounds to Chislehurst, a town that lay twenty miles away. During the time of Henry VIII, when England broke away from Roman Catholic Church in Rome, priests and monks often had to make a quick escape from Henry’s soldiers.

Miss Parker asked us to put on our blazers and follow her outside to an oak tree that stood far away from the house, almost to the skirt of the wood. Its trunk was enormous. I remember the crisp air, the blue sky and the sound of dry leaves cracking underfoot in the juicy green grass. When we reached the oak, there were acorns and chestnuts in their bolls lying on the ground everywhere some cracking open. I spied them because I was standing in a trove of doll-house furniture ready to be made with straight pins and yarn. I filled my pockets. She instructed the whole class to stand in a circle with our backs to the tree. I don’t know how many children we were, probably twenty odd. We calculated from our body measurements that the circumference of the trunk was over 25 feet which would make the diameter of the trunk about 8 feet. One of us tripped backward into a tall triangular hole in the tree. Funny we didn’t see it right away. It was boarded up. This, Miss Parker explained, was a quick escape from the underground passageway from the house through the trunk of the tree. The monks, if they didn’t want to wind up in Chiselhurst, could escape through the tree and run into the wood that stood some yards away.

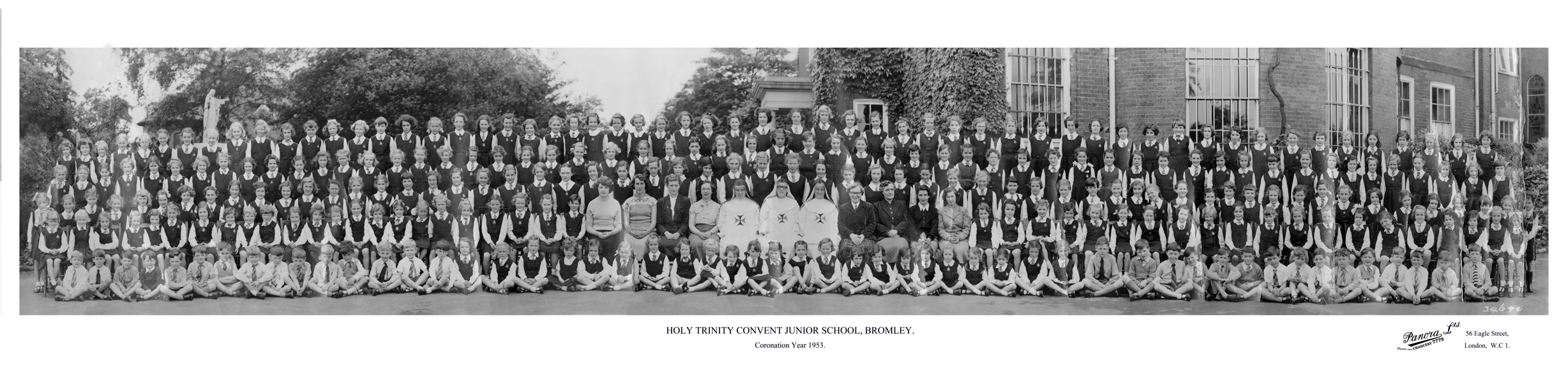

I had to leave to go to boarding school that year,1952, missing most of the Miss Parker experience. The boarding school was also run by French nuns whose young charges were physically ill and needed the sea air and exercise to regain their strength. When I returned home fully recovered in 1953, I stood caught in the icy glare of Miss Dickinson’s blue eye. Six months later my Irish parents would emigrate from England to the States to see what they could see.

Please click on the picture to enlarge. I think you can find Miss Parker– and Miss Dickinson quite easily. You can find me to the extreme right of the picture, second row from the top, seventh little person in.

I was tidying my books and papers the other day and lingered over my old school books. This is why the memory of school days came to mind. I am so grateful for those teachers who were stern and (mostly) kind who taught me how to love learning, how to manage the vast array of things available to learn, sort them out- where to begin, when to end the perusal. My mother and father had a big hand in this. It was their kind thoughtfulness that put me in these schools, paid for them, the uniforms, the books. My mother was a tailor. My father was a welder. There’s a strong streak of artistry that runs in my family. And if I might say, I admire their intelligence. Life did not afford them the opportunity to rise professionally but they were very good at what they did. My father taught me to weld. Three hours of setting a good bead felt like fifteen minutes had passed. Now that’s concentration and control over a thousand tiny little muscles in your fingers, forearms, eyes– and back! My mother taught me organization: When you clean a room start at the corner that is farthest away from the door. Clean the area in a zig zag left to right pattern until you reach the door. The room is now done. Step out of the room and close the door. Apply that rule to everything you do. By the way, I bought you this book. She would sit with me for what seemed eternal summer afternoons, a dictionary as big as a suitcase on our laps. She would pronounce and spell the words. Talk about the meaning. I would follow. Page after page. And long evenings were filled with both my parents who’d recite poetry from memory. Tell stories from history.

Some of those stories were about the Tuatha de Danaan, (Tu-ah-tha de Dan-on) the magical people who lived in Ireland ten thousand years before the idea of writing was a gleam in anyone’s eye. And these magical folks arrived by slender boats. They appeared silently out of the mists, dark skinned, and lithe. Some sat cross legged on leopard skins. My uncle, who was in the Merchant Marine during WWII said he worked with Hindu chaps whose Sanskrit language, especially words related to numbers, were almost identical to the Old Irish language.

The Tuatha de Danaan had musicians, storytellers and poets, physicians, astronomers, soothsayers, priests, planners and advisors in their troupes. The children of the goddess Danu had no chief. They had Dagda, a wise elder. Those who acquired intelligence and skill in various tasks had a voice in planning for the people. Chieftains do not arise unless there is threat of war. Kings, Queens, and chieftains do not stay in power unless war is a constant goal– or threat.

As millennia passed, legend tells us the Irish Druids rose from the people of Danu. They wore rainbow capes, feathered tunics and headdresses. Their magic tool was their voice. They were sages, advisors, scholars in private practice. But over all else, they were poets for which they were accorded divine rank. They had freedom of movement to cross political borders denied even to kings and wherever they traveled they were entitled to the best available lodging. And woe to anyone who harmed or even offended a poet. There is a legend about a wandering poet who visited Tara in the days when gods themselves ruled there and was denied what he considered suitable food and a fine enough bed. The next morning, he entered the throne room at Tara, which was named “Star of the Poets” (Realta na bhFile), and recited five satirical lines of verse, the power of which toppled the surprised king from his throne. The druids’ powerful rhetoric was used either as magical chant which could topple gods or as a less potent poem. They paid no taxes and were exempt from military service.*

Changes loomed as the threat of war grew. Circa 1700 BCE, the Celts were slowly migrating westward toward Ireland from Northeastern Europe and the Gaels were moving northward from Iberia.*** The tribes would eventually meet and The Tuatha de Danaan would be killed off. However, never say die. Irish folklore adamantly maintains that the magical people disappeared back into the mists as they had come. They reside on the island of Tir na Nog, (Tier-nan-Og) a land of youth, abundance and joy that is visible occasionally beyond the shores of Ireland. The island appears out of the mists and disappears back into the mist. It has never been found. They also reside in Ireland as the wee folk who appear occasionally. Plans for city development and major highways have been rerouted around trees believed to be the homes of the faeries.

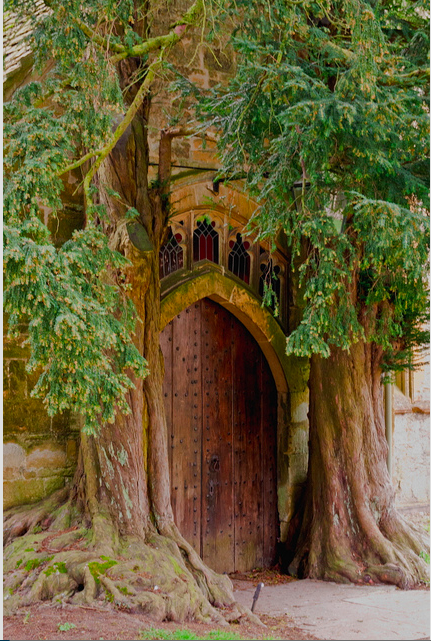

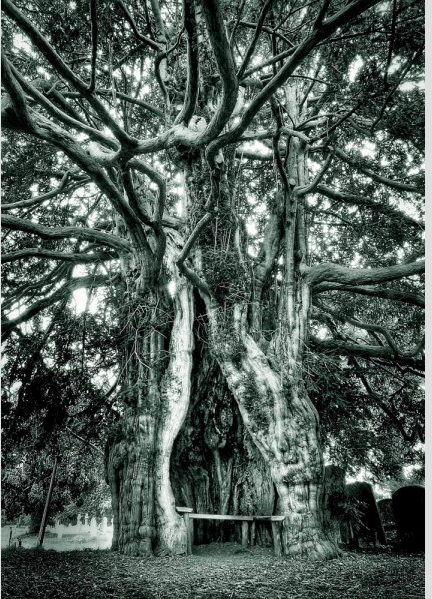

The important trees in Ireland are yew, rowan and hazel.* In England, they are the yew and the oak. The yew’s reputation for long life of hundreds of years is due to the unique way in which the tree grows. Its branches grow down to the ground to form new stems, which then rise up around the old central growth as separate but linked trunks. After a time, they cannot be distinguished from the original tree. So the yew has always been a symbol of death and rebirth, the new that springs out of the old, and a fitting tree for us to study at the begin- ning of a new year. As the days now grow longer with the beginning of a new solar cycle, we move into the future on the achievements of the past, new creativity springs forth grounded in the accomplishments of the years gone by.**

The important trees in Ireland are yew, rowan and hazel.* In England, they are the yew and the oak. The yew’s reputation for long life of hundreds of years is due to the unique way in which the tree grows. Its branches grow down to the ground to form new stems, which then rise up around the old central growth as separate but linked trunks. After a time, they cannot be distinguished from the original tree. So the yew has always been a symbol of death and rebirth, the new that springs out of the old, and a fitting tree for us to study at the begin- ning of a new year. As the days now grow longer with the beginning of a new solar cycle, we move into the future on the achievements of the past, new creativity springs forth grounded in the accomplishments of the years gone by.**

Dearest All~ I send you this new year wish. It is a lullaby to Cormac, a high king of Ireland who, before battle, is sung to sleep by a druid:

High its strain, O Cormac.

Sleep as though in downy feathers.

Cry no blood on your enmity.

Enduring your name above Ireland.

Arise here, changed, silent

by means of me and my intelligence.

Although battle be the waking from the draught of sleep,

attained will be what I establish between us,

obscured the discord jointly come to us,

although battle be its shattering.

O Fair Pinnacle, Flowery One, Stronghold (Ship),

be you most precious among (your) contemporaries

(a pledge to his people’s commonweal).

Toward that, this melody of guardings,

a circle of safe-keepings (around you).

O Cormac, bind yourself to your sleep,

high its strain, O Cormac.*

I wish you all well as you venture forth. This is a new era, a new clime. May you love well. May you sleep well. May you work well.

Your loving friend, Peggy

*http://www.imbas.org/articles/excellence_of_the_ancient_word.html**http://www.druidry.org/library/trees/tree-lore-yew***https://www.legendarytours.com/dates.html

Three things from which never to be moved: one’s Oaths, one’s Gods, and the Truth.

The three highest causes of the true human are: Truth, Honor, and Duty.

Three candles that illuminate every darkness: Truth, Nature, and Knowledge.

— Traditional Celtic Triads

Yew Trees: