|

Snake

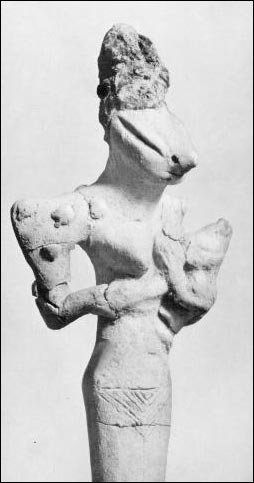

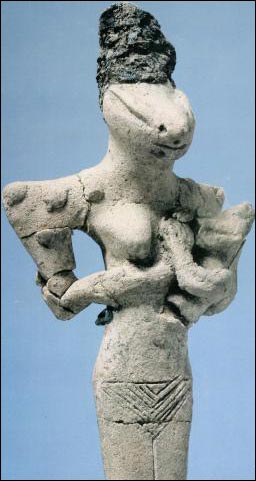

Goddess and Child Date Ubaid 4 Period (first half of the fourth millenium BCE) Artist Unknown Origin The Ancient World : The Middle East : Proto-Historic Chalcolithic Period : Time of Ubaid period and contemporary cultures throughout the Middle : East (i.e. Sialk III, Hissar I, Susa A, etc.) Summary Figures of nude, nursing females with reptilian (often serpentine) faces--their lower legs ceremonially broken off to prevent their escape--are commonly found in the graves of both sexes from the Ubaid period. They seem to represent a chthonic goddess linked with the life-giving, life-sustaining essence of the earth and as well as with the dark, mysterious underworld, land of the dead and source of all life. Description This figure represents a slender female in standing position. Her head is reptilian. She has long, slanting slit eyes, a pointed snout with a nostril on either side, and a small, horizontally slit mouth. She wears a conical bitumen headdress. Her shoulders are very broad (pellets have Peen applied to them, front and back), while her hips and waist are narrow. The pubic area is represented by a large incised triangle. Her legs have been broken off below the knees. She suckles an infant, holding it in the crook of her left arm. The infant also has reptilian features. Cultural Context Female figurines of this type were kept in houses and placed in graves as images of a chthonic mother goddess who gave and sustained life on earth and who might be expected to play a role beneficial to the deceased in the underworld. In the symbolic vocabulary of ancient Mesopotamia, the reptile--most often a snake--was the most common chthonic image: statuettes of the type shown here combine the naked female form of the Great Mother, who brings forth and nurtures all life, with that of the serpent, a symbol of rebirth. Here the maternal aspect of the figure is underscored by the presence of the nursing infant. This female's tall, conical headdress is probably an emblem of her divinity, whereas the pellets on her shoulders resemble both scales and ritual tatoo markings that would be in keeping with her serpentine and otherworldly nature. The presence of figurines of this type in both the houses and the graves of the Ubaid period attests to a belief in some form of existence after death, and, what is more, an existence during which the deceased would continue to rely on the powers that sustain life on earth. The fact that a number of such figurines were discovered at Ur suggests that they represent a goddess whose characteristics were well defined, even during this early period. Both the serpentine and maternal aspects of this figure reflect widespread beliefs in the ancient Near East. The serpent as a chthonic image was especially common in Mesopotamia and Iran. During early periods, chthonic deities tended to assume serpentine and quasi-serpentine forms, while later representations are more commonly (but by no means exclusively) fully anthropomorphic, with serpents or serpentine monsters as adjuncts or divine emblems. As maternal symbols, statuettes such as this one have close links with early neolithic fertility figurines, but display a more attenuated female form. Archetypal Commentary There ere numerous aspects of the image that suggest the experience of rebirth and the nurturing of new life. The most obvious meaning carried by the image is the nurturing of new life, for this snake goddess cradles an infant in her left arm and suckles it. It is commonly known that the ideal place to hold an infant human being is on the left side next to the heart. The rhythm of the heartbeat calms the child by simulating the womb-experience, during which it lived in close proximity to the heart. The milk of the mother is a symbol of the ideal food; if the mother is divine, her food, too, is divine and will bring about the immortality of the child. The serpentine features of this goddess suggest a lunar symbolism. Like the moon, the snake is believed to embody the power of an immortality based on metamorphosis: it appears and disappears; it has as many coils as the moon has days (a legend preserved in Greek tradition); and it sloughs its skin (that is to say, it is periodically reborn just as the moon is). As an epiphany of the moon, the snake can also bestow fecundity. In many cultures, it is believed that snakes produce children. For example, among the Togos in Africa a myth tells that a giant snake dwells in a pool near the town of Klewe and, receiving children from the hands of the supreme god Namu, brings them into the town before their birth. Many goddesses have snake forms, especially goddesses associated with the underworld in any capacity. The Great Goddesses share as much in the sacred nature of the moon as in that of the earth. And because these goddesses are also funeral goddesses (the dead disappear into the ground or into the moon to be reborn and reappear under new forms), the snake becomes very specially the animal of death and burial, embodying the souls of the dead, the ancestor of the tribe, etc. Material or Technique Sculpture: terra-cotta, with bitumen Measurement Height: 5 1/2 in. (14 cm.) Provenance Iraq: Ur, pit F (PFG/AA bis, U.15506) Repository or Site Iraq: Baghdad, Iraq Museum, no.8564 Image Sources Amiet, Pierre, Art of the Ancient Near East (Harry N. Abrams: New York, 1980): pl.24. References Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven, 1976. Leisegang, Hans. "Das Mysterium der Schlange." Eranos-Jahrbuch 7 (1939): 151-250. Lurker, Manfred. "Snakes." The Encyclopedia of Religion. New York, 1987. Mundkur, Balaji. The Cult of the Serpent: An Interdisciplinary Survey of Its Manifestations and Origins. Albany, N.Y., 1983. Glossary EPIPHANY--An appearance, or manifestation, of a deity or any other sacred reality. In Christianity, it is the name of a festival commemorating revelation of Jesus as the Christ to the gentiles in the persons of the Magi at Bethlehem (sometimes called Twelfth Night). |