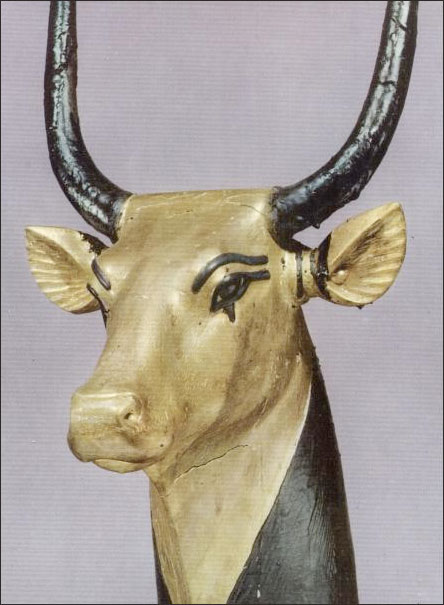

Head of a Cow-goddess

Date

Reign of Tutankhamun Nebkheperure (1347-1337 B.C.)

Artist

Unknown

Origin

The Ancient World : Egypt : New Kingdom : XVIII Dynasty : Amarna and

Aftermath

Summary

This head of the divine cow may reveal either the venerable Hathor (known

as the "golden one") or the local Theban cow-goddess Mehurt

(literally, "great flood") -- or it may imply them both. The

black of the goddess's neck and horns suggests the fertile black silt

of the Nile. A cattle-rearing African people, the Egyptians formed a

theological concept of a "divine cow" with powers of nourishment

and protection. This image offered protection to the deceased Tutankhamen.

Description

The head, carved from a single block, conveys a sense of bovine dignity

and repose (Bothmer, 134). The wood has been covered with a thin layer

of gesso -- the usual Egyptian practice -- and then partially gilded

and covered with a substance described as black varnish. Traces of decoration

may exist beneath this dark finish (Edwards, 12). The head is mounted

on a square wooden plinth painted in the same dark varnish, probably

symbolizing the gloom of the Underworld (Carter, 46; Luxor, 134). The

horns of the cow are lyriform and made of wood covered with a thin sheet

of copper or bronze which was then varnished black. Black glass was

used for the eyebrows and eyes; the pupils are composed of white glass

or limestone spheres inlaid in obsidian or natural black glass. The

eyes are in the form of "the eye of Horus," which symbolizes

a tie with Re, the sun-god (occasionally in the older literature it

is called "the eye of Re"); see Carter, 46).

Cultural Context

It is not surprising that the Egyptians would have formed an important

theological concept around a "divine cow." Both in reality

and as a symbolic form, the cow offered the Egyptians nourishment and

protection. In a general way, the use of black and gold in the present

head undoubtedly signify respectively fertility (in association with

the Nile mud of the annual innundation) and endurance (the quality of

an imperishable metal). The purpose of this sculpture, which was found

in the tomb of Tutankhamun, is uncertain, though clearly it in some

way offered protection to the deceased king. Elsewhere in Tutankhamun's

tomb there are objects carrying bovine imagery and inscriptions mentioning

specific cow-goddesses, but it is not possible to establish positively

which of the major cow-godesses is -- or is not -- being invoked by

the present cow's head. The immediate context of this tomb and also

perhaps the extensive use of black points first to Mehurt, a local Theban

deity, while the gold color and Hathor's own importance as a funerary

deity at Thebes means that it may be she who is invoked here (see also

below).

Egyptian artists explored the natural forms of animals from earliest

times. Their depiction of animal forms, it might be noted, was not to

provide "illustrations or descriptions of appearances," but

rather to serve as "allusions to essential parts of the nature

and function of deities" (Hornung, 113). The nourishment, abundance,

and the "maternal tenderness" associated with cows found expression

in three major goddesses: Hathor, Nut, and Mehurt. It is probably not

possible to ascertain which of these goddesses first assumed bovine

form. In the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom, the name "Mehurt"

is already spelled by using the symbol of the cow (Pyramid Text 289c).

Nevertheless, there are data suggesting that Hathor also used this form

at an early time (Bleeker, 32). Nut, it would seem, is a latecomer to

bovine symbolism, and her use of it is apparently secondary. It is significant

that all three goddesses are associated with the sky in one form or

another, that is, with the primeval sky-ocean which was thought to bring

forth divine life in the sky and in the Underworld. Although the present

object lacks an inscription, its context suggests strongly that it is

Mehurt who is being invoked most directly, even though she is rarely

depicted (the first inscribed depiction of Mehurt is found later, in

the tomb of Tawosret [XX Dynasty, 1196-1080 B.C.], where she is shown

as a woman with a cow's head [Hornung, 111, no. 25]).

Although the rituals associated with Mehurt are lost, certain information

survives. Mehurt in particular was held to be the nocturnal sky or "the

darkness in the night which is in Mht wrt (Mehurt)" (Budge, 124).

The literal meaning of her name ("great flood") suggests an

association with the annual innundation of the Nile, which with its

thick deposit of black silt brought fertility to the seemingly dead

fields. Later myth credits her with several acts of creation, the most

important of which was the birth of the sun-god. Upon giving birth to

Re, she placed him -- in the form of a disk -- between her horns (The

Book of the Dead, XVII, 34:35). The absence of a solar disk on the present

head from Tutankhamun's tomb may reflect damage, or, if this head is

of Mehurt, may be a deliberate reference to the myth of the birth of

Re from Mehurt: i.e., the disk would appear only after the deceased

Tutankhamun as "son of Re" had reenacted his father's birth,

in order to enter into eternal life. Mehurt's ties with other goddesses

tend to obscure her individuality. Spell 186 of The Book of the Dead

refers to Hathor and Mehurt in similar terms: "Veneration of Hathor,

the mistress of the West; kissing the ground before Mehurt" (cited

in Bleeker, 32). Both goddesses are called the "eye of Re"

(although only with Hathor does this epithet seem to refer to the power

to protect Re and do his bidding). Unlike Hathor, Mehurt never created

her own cult, but rather remained known through myths preserved in arcane

religious texts or through occasional paintings or reliefs (she is always

shown as a cow or a cow-headed woman). No cult centers such that of

Hathor's at Dendera are linked with her. In Tutankhamun's tomb the affiliation

between Mehurt and another goddess is well attested: an inscribed bed

found there invokes the abbreviated name "Isis-Mehut," probably

a shortened form of "Isis-Mehurt" (Edwards, 13-14).

During the New Kingdom Hathor gained ascendancy over the other cow-goddesses,

who were gradually absorbed into her iconography and cult; it is plausible

therefore that the present cow's head represents Hathor as tutelary

deity of the Theban necropolis, where she had an ancient cult (at Deir

el-Bahari). The gold color of the head may symbolize a connection with

Hathor, one of whose epithets was "the golden one" (Edwards,

12). As a bovine goddess Hathor could be portrayed as a cow's head emerging

from a hillside, "seemingly beckoning the deceased to pass with

her into the realm of the dead" (Bothmer, 134). In a further elaboration

of this imagery, special temples were cut from the living rock to house

this image of the goddess, fashioned so as to make her "emerge"

from the very hillside.

Archetypal Significance

"The great Egyptian cow goddess is 'the watery abyss of heaven';

Mehurt, one of her variants, gives birth to the sun god....If we recall

the Egyptian forms of the Terrible Mother -- Am-mit, the devourer of

souls at the judgment of the dead, Ta-urt, and the goddesses of the

gates of the underworld -- it will not surprise us that the judgment

of the dead should take place in the hall of Mehurt. This is one more

indication of the original universality of the Egyptian Great Goddess,

who also encompasses the underworld and the watery abyss. For in her

character of Hathor, the Great Goddess is not only the 'house of Horus,'

i.e., goddess of the eastern sky, where Horus, the sun, is born, but

also the cow of the western mountain, the goddess of the dead"

(Neumann, 218-219). The black silt from the annual flooding of the Nile

and the gold of the sun have produced the basic food requirements of

the Egyptians for six thousand years. These two colors as used in the

present image symbolize a union of opposites -- of earth and sky, night

and day, death and life -- which generates energy and the renewal of

life itself. HWP

Special Qualities

Partial depictions of animals are quite rare in Egyptian art (Edwards,

12).

Story

A special text exists which relates the exploits of the divine cow.

It is part of the series to texts loosely known as The Book of the Dead.

These texts comprised individual works such as The Amduat, or That-which-is-in-the-Underworld,

The Book of Gates, and The Book of Caverns. In The Book of the Divine

Cow, the goddess Nut was transformed into a divine cow who carried the

sun-god Re to Heaven on her back. Portions of the earliest known version

of this book are inscribed on the interior rear panel of the outermost

of the huge golden shrines which enclose the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun

(see Piankoff).

Material or Technique

Sculpture: wood, gessoed and gilded; black resin [throat], sheet copper

covered with black varnish [horns]; glass [eyes, eyebrows]

Measurement

Height, 93 in.; width (across horns), 17.5 in. (93, 44.5 cm.)

Provenance

Egypt: Thebes, West Bank necropolis, tomb of Tutankhamun, KV 62, treasury

Repository or Site

Egypt: Luxor, Luxor Museum of Ancient Egyptian Art, no. J.5 (Cairo JE

60736; T.395)

Image Sources

Desroches-Noblecourt, C., Tutankhamen: Life and Death of a Pharaoh (New

York Graphic Society, Greenwich, CT., 1963), color pl. XLVIII

References

Bleeker, C.J., Hathor and Thoth. Two Key Figures of the Ancient Egyptian

Religion (Leiden, 1973)

Bothmer, B., The Luxor Museum of Ancient Egyptian Art, a Catalogue (Cairo,

1979)

Budge, E.A.W., The Book of the Dead (London, 1951)

Carter, H. and A.C Mace, The Tomb of Tut-ankh-amen (London, 1923-1933)

[3 vols.]

Desroches-Noblecourt, C., Tutankhamen (New York, 1963)

Edwards, I.E.S., Treasures of Tutankhamen (London, 1972)

Neumann, E., The Great Goddess: an Analysis of the Archetype (New York,

1955) [trans. R. Manheim; Bollingen Series 47]

Piankoff, A., The Shrines of Tutankhamen (Princeton, 1962)

Glossary

BITUMEN - Pitch or a petroleum tar, occurring naturally; the

ancient Egyptians occasionally used it as an inlay or pigment to color

objects. Many of the extant examples of such objects are funerary in

purpose, which suggests that the blackness symbolized the rich, regenerative

forces of the Underworld.

BOOK OF THE DEAD - The 19th-century German term for the Egyptian

funerary texts (spells, incantations, prayers) written on papyrus rolls

and first appearing during the New Kingdom. Often illustrated, these

guidebooks to the next world were popular heirs to the earlier Pyramid

Texts (for Old Kingdom pharaohs) and Coffin Texts (for kings and nobles

of the Middle Kingdom).

HATHOR - "House of Horus," probably the most versatile

Egyptian goddess. She was protector of the dead (especially in Thebes),

special goddess to the pharaoh, and goddess of music, inebriety, and

dance; often called "Eye of Re," she was as well mother of

Horus in his sky-god form. She appears as a cow, tree, or a woman with

cow's horns and sun-disk (and holding a menat-collar and a sistrum,

or ceremonial rattle).

NUT - Ancient sky-goddess with a funerary aspect. Her image

frequently took the form of a woman arching over Geb, the male earth-god.

She gave birth to the sun each day and then swallowed him each evening.

She could also appear as a cow, a woman wearing a starry dress, or a

tree from which a woman emerges with a tray of viands.

PYRAMID TEXTS - Spells, prayers, and incantations inscribed

in interior rooms of certain Old Kingdom pyramids (beginning in the

V Dynasty). Exclusively royal, they were meant to aid the deceased Egyptian

kings in their transformations after death (they were superseded in

this function by the Coffin Texts and then by the Book of the Dead [Going

Forth by Day]).

|